The voice of my beloved! Look, he comes, leaping upon the mountains, bounding over the hills. My beloved is like a gazelle or a young stag. Look, there he stands behind our wall, gazing in at the windows. My beloved speaks and says to me: ‘Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away; for now the winter is past, the rain is over and gone. The flowers appear on the earth; the time of singing has come, and the voice of the turtle-dove is heard in our land. The fig tree puts forth its figs, and the vines are in blossom; they give forth fragrance. Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away. Song of Songs (Solomon), 2.8-13, New Revised Standard Version of the Bible.

The voice of my beloved! Look, he comes, leaping upon the mountains, bounding over the hills. My beloved is like a gazelle or a young stag. Look, there he stands behind our wall, gazing in at the windows. My beloved speaks and says to me: ‘Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away; for now the winter is past, the rain is over and gone. The flowers appear on the earth; the time of singing has come, and the voice of the turtle-dove is heard in our land. The fig tree puts forth its figs, and the vines are in blossom; they give forth fragrance. Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away. Song of Songs (Solomon), 2.8-13, New Revised Standard Version of the Bible.

North Hill towers above Minehead in West Somerset. While Minehead is regarded as gateway to Exmoor, North Hill, with its magnificent views of coast and moorland, is pure Exmoor. Deep in a combe in the western part of North Hill is a small hut where walkers can stop, rest and take shelter. It is a ‘wind and weather’ hut built in 1878 in memory of Sir Thomas Dyke Acland, former landowner, who, for over half a century, took his children and grandchildren to the combe where the hut is situated ‘ training them in the love of nature and Christian poetry.’ One of the poems engraved on the hut’s walls is by nineteenth century priest and poet John Keble reads:

Needs no show of mountain hoary,

Winding shore or deepening glen.

Where the landscape in its glory

Teaches truth to wandering men.

Those of us who live on Exmoor will instinctively understand what the poet means when he says the landscape ‘teaches truth.’

Those of us who live on Exmoor will instinctively understand what the poet means when he says the landscape ‘teaches truth.’

Over the last two years, a number of Ukrainian families have come to Exmoor and Minehead, having fled their country because of the war with Russia. One Ukrainian spoke to me of the joy and delight of living on Exmoor commenting that its beauty had a healing power. As he spoke, I thought of the devastation that his beloved country with its lively communities and rich farmlands was facing. But he was right. There is a healing power in the beauty of Exmoor which refreshes and inspires body, mind and spirit. The one million visitors who flock here each year to rest, search, explore and follow their passions testify to the healing power of Exmoor.

Love, beauty, delight, joy, healing, searching and passion reflected in our surroundings are all themes that figure highly in the book from the Bible quoted above. That book is called the Song of Songs, also known as the Song of Solomon and was compiled around 2.500 years ago. It is a beautiful and intriguing book, found in the Hebrew Scriptures, also known as the Old Testament. The book is not read very much in churches these days, though at one time it was very popular. One of the reasons for its neglect is that some within the Church are a bit embarrassed by it and are not sure what to do with it: this has been its fate ever since it was put into the Bible. One reason for the embarrassment is that it is made up of twenty-three love poems, some very passionate, which are stitched together. Opening the pages of the Song of Songs is like walking into an art gallery where all the paintings are on the theme of love and beauty as described through the relationship between two lovers and the world of nature. The pictures in the gallery depict highs and lows, ecstasy and pain, life and energy. Each painting stands in its own right, but together they build up a sense of the celebration of love and beauty, the interdependence of all creation and the challenge that this brings to humanity as it is currently lived. In addition, the exhibition points the viewer through and beyond the experiences depicted on the individual canvases to something far greater and mysterious.

Another reason for embarrassment of the book is that while it’s centred around God’s relationship with his people and God’s presence is evoked by what we read, it never directly refers to God. I suppose one can understand people in church and synagogue raising questions about a book in the Bible that is made of love songs and doesn’t make reference to God.

The book has been a particular favourite of mine for many years, but since living on Exmoor, I have found myself drawn to it more and more. I have come to realise that even though the poems were written and compiled in the Ancient Near East and shed light on that context, they also shed light on Exmoor. While some of the natural landscape in the book is native to the lands of the poems’ origins, the sentiments and blossoming energy can be found on Exmoor.

The book has been a particular favourite of mine for many years, but since living on Exmoor, I have found myself drawn to it more and more. I have come to realise that even though the poems were written and compiled in the Ancient Near East and shed light on that context, they also shed light on Exmoor. While some of the natural landscape in the book is native to the lands of the poems’ origins, the sentiments and blossoming energy can be found on Exmoor.

But there is more. As we shall see, as well as shedding light on Exmoor, the Song of Songs also sheds light on the Climate Debate which affects not only Exmoor but our whole planet. The Song of Songs , without doubt, is the most ecological book of the Bible and speaks into the current debate in a surprisingly radical and challenging way.

So, what is it about? The book does not explicitly answer this question, but when its earliest readers heard, from a holy book, the story of two lovers, they would immediately have recognised that they were listening to a reflection on God’s love for his people written in such a way as to evoke divine resonances within human love. Furthermore, the original readers did not need to hear the name of God – they would have known.

What is important for us today is that we hear not only what the Song of Songs is saying, but also hear the way it is expressing it. Bearing this in mind, I want to highlight briefly two challenges – and there are more – that this book throws at our care of Exmoor and our planet.

First, there is the recognition and appreciation of beauty: the beauty of people, the beauty of Exmoor and the beauty of our planet which are all related. Linked with this is the need to argue that the appreciation of beauty should be a foundational element in our striving for the survival of our world. As one commentator points out, ‘Beauty quickens the heart, arouses the senses, stirs the imagination and inspires praise…..in the face of beauty, the self dissolves and the observer merges with the observed.’ The people we love are always beautiful to us, no matter how young or old they are and we are willing to do anything to help them flourish. Beauty draws us into action.

Beauty in the Song is visual, aromatic and tactile – it is not something that is abstract and idealised – and it affects characters in the book so strongly that they want to act for the good of the object of beauty. The word ‘beauty’ occurs more in the Song of Songs than in any other book in the Bible. We read of the beauty of the two lovers and what is remarkable is that the beauty of the lovers is derived from the beauty of the land. In other words, the lovers and the land are regarded as beautiful and the beauty of the people is related to the beauty of the land. For example, the woman is told – and, while these words have been the butt of many jokes throughout the ages, they would originally have been regarded as compliments – ‘How beautiful you are, my love, how very beautiful! Your eyes are doves…Your hair is like a flock of goats….Your teeth are like a flock of shorn ewes.’ (4.1-2) Similar words are addressed to the man, again drawing on the beauties of the land.

French aviator and philosopher Antoine de Saint Exupéry wrote, ‘If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.’ Similarly, arguments about sustainability and economics are, of course, important, but, what is more important is that if we want to move people to action, we need to use the language of beauty and delight.

Secondly, many would argue that human beings have lost, especially over the last one hundred years or so, our connection with nature. In a document published in 2015, Pope Francis describes the loss of connection in this way:

Mother Earth cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her. We have come to see ourselves as her lords and masters, entitled to plunder her at will.

The Song of Songs makes it clear that the there is an interdependence between human beings and the earth. We have already seen the closeness of the relationship between human beings and nature when hearing how the beauty of the lovers is derived from the beauty of the land. The Song also reminds us that humans will flourish when the environment flourishes. As we have heard, love blossoms when ‘the winter is past, the rain is over and gone. The flowers appear on the earth; the time of singing has come, and the voice of the turtle-dove is heard in our land.’ (2.11-12) The interdependence between human beings and the earth is something which we are learning and it is something that lies at the heart of the Song of Songs. The natural world does not revolve around human beings, the Song intimates, but there is a loving mutuality. When we are friends with the earth, we all win.

I want to leave the final words to the Song of Songs. The poem on the Acland wind and weather hut on North Hill claims that the landscape in its all its glory, ‘teaches truth to wandering men.’ In the last chapter, the compiler of the Song of Songs draws out some truths from the love poems he, or she, has quoted:

For love is as strong as death, passion fierce as the grave. Its flashes are flashes of fire, a raging flame. Many waters cannot quench love, neither can floods drown it. If one offered for love all the wealth of one’s house, it would be utterly scorned. (8.6-7)

Image 1 – Exmoor stag.

Image 2 – Wind and Weather Hut, North Hill, near Minehead.

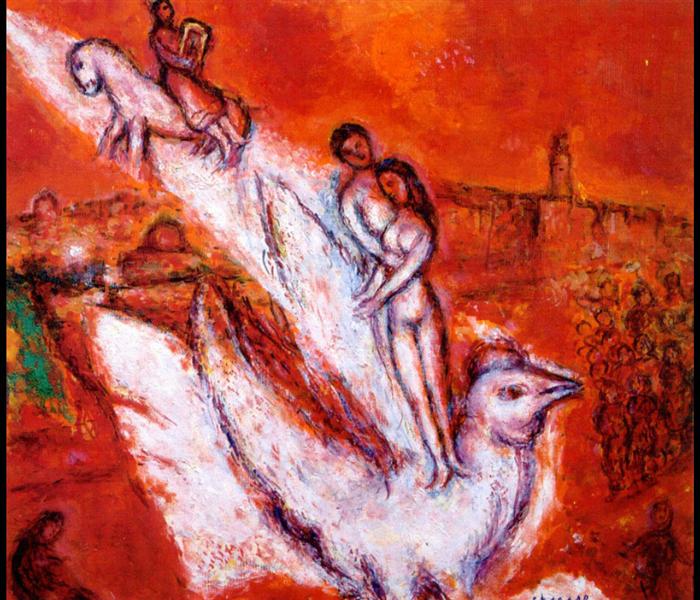

Image 3 – Song of Songs by Marc Chagall.

Talk given at St. Luke’s, Simonsbath, Somerset, for the Simonsbath Festival Service 2024

Acknowledgement: I am indebted to the writing of Ellen Bernstein who has opened up a new way of viewing the Song of Songs. I draw on her thinking in this piece. Ecologist, teacher, author and Rabbi, her passion is to show that the environmental crisis is, at heart, a spiritual crisis.